Modern hair transplants generally produce quality results. However, the biggest disadvantage of hair restoration remains the fact that people have limited donor hair at the back of their scalps in the safe “permanent” zone.

Men with large bald areas will usually not get great results from a hair transplant unless their coverage expectations are modest. Meaning that they do not mind seeing barren scalp on days when their hair becomes wet in the rain or disheveled by the wind.

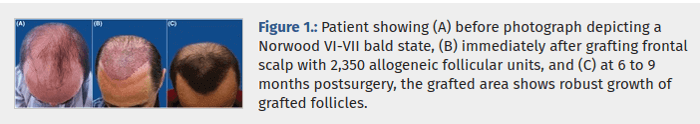

Hence the common question: “Can you transplant hair from one person to another?”. i.e., allogeneic hair transplants.

Person to Person Hair Transplants

Because of this lack of sufficient donor hair supply, one would wonder why person to person hair transplants have not become more common?

The obvious and most cited explanation from hair transplant surgeons is that due to the requirement of taking anti-rejection medications (immunosuppressants) for life, person to person hair transplants are almost never approved. Taking immunosuppressants for life carries significant health risks.

However, from what I have read in numerous organ transplant stories, death from taking anti-rejection drugs is rare. People monitor themselves daily when taking such drugs. I wonder how many people below the age of 60 die from the side effects of taking immunosuppressants?

Moreover, it seems like physicians are getting closer to weaning organ recipients off of immunosuppressants entirely. That would be a miracle. In any case, even if proven to be very safe in the long run, most people would not want to take immune supressing drugs just to get more scalp hair. Therefore, I was not planning on writing a post about person to person hair transplants.

Jahoda and Reynolds: First Successful Hair Transplant Between People

However, yesterday, I happened to reread the summary of a groundbreaking experiment from 1999 by Dr. Colin Jahoda on his wife Dr. Amanda Reynolds. The actual study was published in Nature.

Dr. Jahoda transplanted several of his scalp hairs to Dr. Reynolds arm, and four hairs then grew on Dr. Reynolds arm. I read about this well known experiment numerous times in the past, but forgot to ever check if Dr. Reynolds took immunosuppressants. Then I read the below in the above linked article and felt like a lightening bolt struck me:

Apart from its theoretical use in cosmetic medicine, the experiment reveals that: hair follicles are one of the rare tissues apparently capable of being transplanted from one body to another without rejection. Why evolution has endowed them with such “immune privilege” is a mystery.

This makes me wonder why more surgeons have not attempted person to person scalp hair to scalp hair transplants? In one of my pasts post on transplants and immunosuppressants, one commentator suggested that you could never get another living person to donate his or her hair to you. I think that is absolutely incorrect. If I had a very full thick head of hair and someone offered me say $100,000 to donate 20 percent of my scalp hair, I would be more than happy to do so. If it were a family member, I would do it for free.

Going back to the above article, it seems like Dr. Jahoda transferred dermal sheath cells rather than actual hair. However, the full hairs were extracted from Dr. Jahoda’s scalp prior to extraction of the dermal sheath cells from them via the use of a powerful microscope. Dr. Jahoda holds a patent on this procedure. The doctor did have some doubts about normal hair cycling feasibility after one round of shedding was over.

Success not Guaranteed

I was excited by my finding after re-reading the summary of the Jahoda experiment. Nevertheless, considering that it all happened in 1999, I think there must be some sound explanation behind person to person transplants never taking off.

I did some more googling on this, and came across an interesting comment from 2009 that is pasted below. Usually, I do not like to quote comments from internet based forum members. However, this one from Marion Landan on the regrowhair site seems somewhat legitimate and sincere to me:

“Just want to correct what you are saying about hair transplanting from another person. The people do not have to be identical twins or even related to one another. I have been told by a retiring hair transplant expert who tried some of these surgeries that sometimes it works and sometimes it does not.

Just as there was a learning curve for transfusing blood, there are things not understood about why hair can be transplanted sometimes from an unrelated donor, and sometimes can’t even be transplanted between identical twins (possibly with the twins the bald brother had an infection that caused his original hair loss, after transplantation from his brother, his head swelled up and rejected the new hair). I have also been told that hair transplanting between people was made illegal in the United States several years ago — so doctors no longer try it.”

Why would this have been made illegal? Were there serious side effects involved?

Reducing Rejection Rates after Transplant

Half of Dr. Siemionow’s prediction came true in 2015: first ever skull and scalp transplant.

Finally, it seems like certain commonalities between donor and recipient might increase the likelihood of survival of organs and tissues after a transplant. These can include blood type, certain common genes and more. Transplant survival rates with or without anti-rejection medication will continue to improve as researchers uncover more such details.